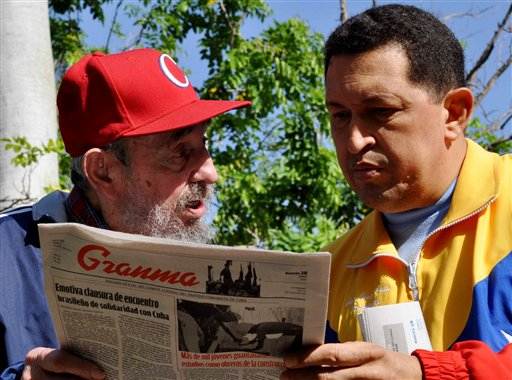

Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez’ July 1 announcement that he is ill and may not return from Cuba for several months has threatens to send Latin America’s biggest oil producer into a political tailspin, which would seriously affect the strategic dynamics in the region, possibly forcing Brazil, the region’s dominant player, to take a more assertive stance to maintain stability.

In principle, the potential end of Hugo Chavez’ reign in Venezuela is welcome news. Markets rallied after his 15-minute speech, sparking hopes that a new leader would loosen the government’s grip on the increasingly paralyzed economy, allowing for investments to return to the country. His removal from power would also severely weaken the dictatorial Castro regime in Cuba, which has received an estimated US $3.5 billion in oil subsidies from Venezuela last year, and which may face financial collapse should a new Venezuelan government decide to stop the subsidies, which are deeply unpopular in Venezuela.

Yet should Chavez really be unable to return to power over the next months, the country could plunge into political chaos, possibly leading to a military takeover, which would be a severe setback for democracy in the region. To begin with, it is entirely unclear who would replace Chavez, as the constitution (written by himself) allows him to appoint either the vice president or anyone else. Since Vice President Elías Jaua is widely seen as a colorless dogmatist, potential candidates include, among many others, Chavez brother, Adán Chavez, or his daughter, Maria Gabriela. Yet none of them seems to have Hugo Chavez’ skill to hold together a party that includes many competing interest groups. In addition, the government’s popularity has been battered by an unending series of problems, including blackouts, food and housing shortages, high rates of crime, a lack of economic growth, high inflation, prison riots, widespread corruption, and no clear plan how to get out of the mess. Even a healthy Chavez would face a bitter election battle in 2012, as his country is worse off on virtually all counts than when he was first elected in 1998. Now, with the nation’s attention focused solely on their leader’s health, all of the problems named above – crime and inflation being the most serious – are bound to get worse still due to the leadership vacuum in Caracas.

Paradoxically, the new situation does not make life for the opposition any easier. Personal calamity often causes increased popularity, as recently seen in Argentina, when Cristina Fernandez de Kircher’s approval rating surged after her husband’s  unexpected death. Criticizing Chavez may thus backfire and make the opposition seem inhumane at a time when millions of poor Venezuelans pray for their leader’s recovery. In addition, an election without Chavez as a candidate would render the opposition’s anti-Chavez platform useless, forcing it to adapt to a post-Chavez Venezuela, considerably more difficult to navigate. At a time when the country’s democratic institutions are already severely strained, a fair election victory against the incumbent would be an important step towards reestablishing democracy in Venezuela; yet this scenario seems distant at this point.

unexpected death. Criticizing Chavez may thus backfire and make the opposition seem inhumane at a time when millions of poor Venezuelans pray for their leader’s recovery. In addition, an election without Chavez as a candidate would render the opposition’s anti-Chavez platform useless, forcing it to adapt to a post-Chavez Venezuela, considerably more difficult to navigate. At a time when the country’s democratic institutions are already severely strained, a fair election victory against the incumbent would be an important step towards reestablishing democracy in Venezuela; yet this scenario seems distant at this point.

Complicating matters further, the a senior military general declared recently that the military were “wedded” to the revolution and would not accept an opposition government. Under Chavez’ Bolivarian Revolution, the military established itself as an important political actor, and it remains to be seen how willing the generals are to see their power reduced under a new administration. In a country awash with guns and several radical factions, serious political strife could emerge in urban areas, turning Venezuela into a rudderless ship.

In such a case, Brazil would be the only actor potentially able to contain a fallout. Brazil has important economic interests to defend: Bilateral trade between the two in 2010 has been US $ 4.6 billion, and many companies such as Odebrecht and Petrobras have made large investments in the country. While a mercurial Chavez has lambasted investors from many countries and nationalized their operations, he has traditionally been kind to Brazilian undertakings, allowing them to reap huge benefits in a markets with little competition. Yet despite their close alliance, the Brazil’s President Dilma Rousseff only found out about Chavez’ health after he addressed the nation on television. In order to help stabilize the political situation and avoid a military takeover, Brazil must closely accompany and work with key figures in Venezuela’s government, the military, and the opposition movement. Brazil has shown before that it can positively influence its neighbors and avoid political turmoil – for example in Paraguay – and it may be well advised to position itself again as an honest broker between Venezuela’s factions, should they be unable to pave the way towards a stable political future.

Read also:

Brazil and the dilemma of regional leadership

Can Brazil learn to manipulate China?

Why São Paulo needs a foreign policy

Photo credit: Cortesía Estudios Revolución