The 10th BRICS Summit, set to take place in Johannesburg next month, will not generate as much buzz as in 2011, when all members of the grouping grew at enviable rates, or in 2014, when the BRICS controversially closed ranks behind Russia after growing tensions between Moscow and the West in the aftermath of the Crimea crisis. And yet, those who believe the meeting will be shaped by nostalgic memories of past glories are profoundly mistaken. “Overall, the last decade saw a steady increase in the depth and breath of BRICS cooperation, which consolidated and strengthened the role of BRICS as a unique and important global governance institution”, Alissa Wang of the University of Toronto’s BRICS Research Group recently wrote. Largely seen as an oddity of little consequence, the outfit remains one of the most misunderstood and underestimated structures in mainstream foreign policy analyses.

There are four dynamics to watch at the upcoming summit:

1) BRICS governments will depict the grouping as a reliable pillar of global order

First, the BRICS Summit Declaration will seek to contrast recent US policies vis-à-vis global rules and norms and project the grouping as the guardians of order. The Chinese government, in particular, in exuding optimism. Donald Trump’s unpredictable foreign policy, most recently visible in the realms of nuclear proliferation and trade, dramatically reduce the extent of global scrutiny China faces these days, be it for its mercantilistic trade policies or domestic challenges. Quite remarkably, Xi Jinping has so far won the battle of narratives against Trump, and the Chinese leader is by many regarded as a global stabilizer and defender of global rules and norms, while Trump is seen as a source of risk. As Thorsten Benner recently commented on Angela Merkel’s trip to Beijing, her “preference would be to work in tandem with US on pushing for greater Chinese openness. But as Merkel heads to Beijing, she has no other choice but to hedge against worst of Trump’s excesses.” A very similar dynamic occurs with other BRICS countries, who have misgivings about Chinese trade practices, but who are too dependent to strongly make their case more forcefully — and who are even more worried about what the United States will do to the global trading system.

2) Focus on intra-BRICS cooperation and internal trade imbalances

Yet common concern about US policy and dependence on China is not the only thing that binds the BRICS. The grouping’s major achievement, the New Development Bank (NDB), is finally operating and may soon accept additional members to increase the institution’s capacity. The Bank has approved more than US$ 5 billion in financing for infrastructure projects, including the first non-sovereign loan to Petrobras, Brazil’s oil firm. The BRICS’s National Security Advisors meeting now ranks as one of the most important venues to discuss geopolitical challenges in Asia. Countries will seek to reduce non-tariff barriers amongst themselves and seek to further promote so-called “people-to-people” ties, which improved markedly over the past decade, but which remain well below what they could be.

For South Africa and Brazil in particular, the summit is a crucial moment to address misgivings about trade imbalances. As Tebogo Khaas wrote on a South African news website recently,

(…) South Africa’s role in Brics can best be described as an act of unrequited economic and political benevolence to (…) China. Our participation in Brics seems to primarily be to lend credence to the association and enable access by China (….) to Africa’s commodities – including votes at the UN. However, it otherwise prostrates Africa as a docile consumer market for (….) Chinese goods and services.

Such comments, paradoxically, reinforce why the BRICS grouping is so important for South Africa. Without membership, South Africa’s trade relationship to China would be exactly the same, but it would lack the privileged access to China’s political leadership it enjoys throughout the year during ministerial and presidential meetings. Both South Africa and Brazil can be expected to bring up the issue with Xi Jinping.

3) President Ramaphosa’s first major summit

The summit will also be a unique opportunity for South Africa’s new President Cyril Ramaphosa to tell the international community how he seeks to turn around his country’s fortunes. Ravaged by a never-ending string of corruption scandals, South Africa under Jacob Zuma had gone from global hopeful with lots of potential to utter disappointment in the eyes of most international observers. Yet the summit also matters for domestic reasons. The gathering in South Africa, which includes global heavy-weights such as Russia’s Vladimir Putin, Narendra Modi and Xi Jinping, will be a unique opportunity for Ramaphosa to look statesmanlike — far from trivial considering that Zuma’s successor faces an election in 2019 and will have little time to convince South Africans that he deserves a full term.

4) Brazil is preparing for the BRICS presidency in 2019

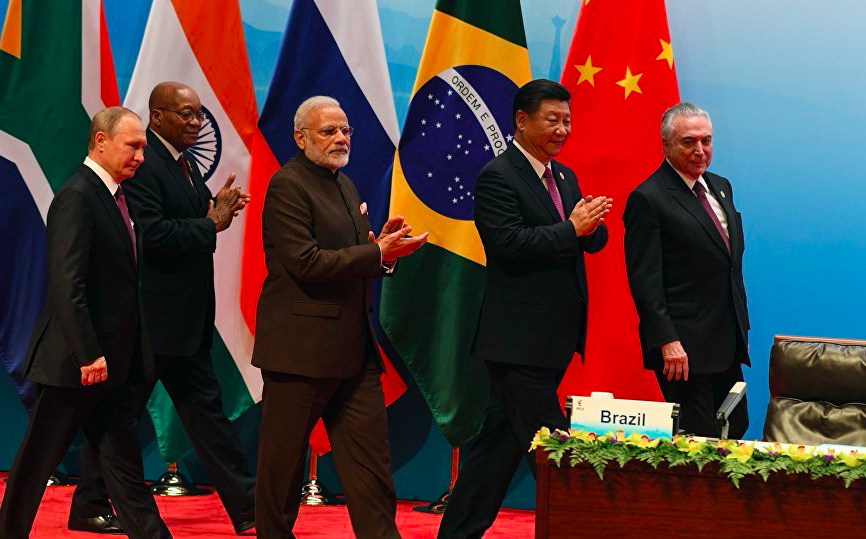

In the weeks before last year’s BRICS Summit in Xiamen, political instability in Brazil was so high that Temer’s mere presence at the summit could be regarded as a success — particularly after the canceled his trip to Hamburg for the G20 Summit, only to change his mind at the last minute. This year again, a diminished Temer will represent Brazil, limping to the finish line of his lackluster term. This strongly limits Brazil’s capacity to shape debates at the meeting. And yet, Ramaphosa’s performance at the Summit will be closely followed by Brazilian diplomats. After all, it will be up to the winner of this year’s presidential contest in Brazil to host the 11th BRICS Summit, scheduled for October 2019. Contrary to the South African president, whoever succeeds Temer will have a full four-year mandate, and can thus benefit even more from hosting the BRICS countries’ presidents, aside from the leaders of the Pacific Alliance and Mercosur, who will be invited to join the second half of the meeting (generally called ‘regional outreach’). If prepared properly, it could be quite an impressive start on the foreign policy front for Brazil’s next president.

Read also:

The BRICS Leaders Xiamen Declaration: An analysis

New Development Banks as Horizontal International Bypasses: Towards a Parallel Order?

‘Post-Western World’ now available in Chinese (Beijing Mediatime)