[This article was originally published in Portuguese in EL PAÍS].

As Brazil’s economic dependence on China grows and tensions between the West and China grow, Brasília will have to navigate an increasingly complex geopolitical scenario

The mood in Western capitals about China is undergoing an unprecedented change. Those optimistic about the consequences of China’s rise are being pushed aside to those who worry the West needs to adopt a far tougher strategy to defend itself against growing Chinese influence. Two recent publications symbolize this change. In Germany, the report “Authoritarian Advance: Responding to China’s Growing Political Influence in Europe”, published by MERICS and GPPi, two important think tanks based in Berlin, argues that China’s rapidly increasing political influencing efforts in Europe and the self-confident promotion of its authoritarian ideals “pose a significant challenge to liberal democracy as well as Europe’s values and interests.” In the United States, Kurt Campbell and Ely Ratner, two former high-ranking US diplomats, published “The China Reckoning: How Beijing Defied American Expectations” in the magazine Foreign Affairs, and argue that US policy towards China since World War II has been hopelessly naïve, and that Beijing has continuously outfoxed the West.

In Australia, the government changed foreign investment rules in response to reports about campaign donations ahead of the 2016 elections coming from businesses with ties to China’s Communist Party. In a dramatic gesture, the Australian prime minister has hit back at China (Australia’s greatest trading partner and major investor in the country) over the issue of foreign interference, speaking Mandarin on television and invoking a famous Chinese slogan to declare Australia will “stand up” against meddling in its national affairs. The consequences of growing tensions between China and the West for global order cannot be overestimated and will affect everyone.

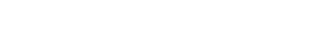

China’s growing economic role is also an undeniable reality in Brazil. We increasingly depend on Chinese demand for commodities, and China will soon turn into the largest investor in Brazil, lending it an unprecedented degree of economic and political influence. The same is true across our neighborhood. While China is pouring investment into Latin American economies, the US government is planning to cut aid projects and speaks of erect walls. China’s growing role across Latin America is accentuated by Washington’s stunning retreat from the region, allowing Beijing to fill the resulting vacuum almost unopposed. Brazil has little choice other than operating within these structural constraints. The question is not whether to embrace this reality of growing dependence, but how to manage it so that it benefits Brazil’s strategic interests.

Growing tensions between the West and China offer a world of opportunities for Brazil if it can learn how to navigate in this new geopolitical environment. Yet at a recent gathering of China watchers in Brasília, participants from government, academia and the private sector openly agreed that Brazil lacked a clear strategy vis-à-vis China. That is partly because domestic challenges currently reduce Brazil’s room for maneuver in the foreign policy realm. Yet a more worrying reason is that the fundamental nature of Brazil-China ties today is one of profound knowledge asymmetry: China knows a lot about Brazil, while Brazil knows very little about China. The consequence? China heavily invests in training an elite of analyst with a sophisticated understanding of Brazil — including precise goals about how many Chinese should learn Portuguese. Brazil, by comparison, lacks a comparable grand strategy. How many sinologists do we need by 2030? How many Brazilian students do we want to have spent time at Chinese universities by 2030? How many Chinese tourists should come to Brazil per year in 2020?

This already has real-life consequences: In Brasília, it is now common for Brazilian government officials – for example, at the Ministry of Development Industry (MDIC) to find out that a Chinese investor interested in a big project has already been in touch with Itamaraty, Planalto, FIESP and several state governors to make his case. That allows Chinese investors to operate in Brazil and strike deals in a way a Brazilian investor in China could only dream of. Any debate about articulating a coherent China strategy must start with investing heavily in closing this knowledge asymmetry. That involves large-scale exchange programs to create a Brazilian elite that is knowledgeable and aware of China, public funds for independent China-related research, and possibly a separate career track for Brazilian diplomats who focus on China to assure that a larger group of Brazilian diplomats fluent in Chinese are based at the Embassy in Beijing at any time, as well as our Consulates across China.

If managed right, the bilateral relationship can be richly rewarding. China’s rise provides opportunities to tap into its immense financial reserves for its own investment priorities and loans when needed – to modernize Brazil’s infrastructure, a key obstacle to increasing Brazil’s competitiveness in the global marketplace. It is thus in Brazil’s interest not only to be an active member of the AIIB, the NDB, but also of China’s Belt-and-Road infrastructure program – determining, at the same time, clear limits to Chinese political influence in Brazil’s domestic affairs. No other country in Latin America stands more to benefit from Brazil from a more connected region – provided that investments are allocated broadly in Brazil’s economic interests.

Managing the relationship to China requires investment in knowledge of historic proportions. Only if we gain a profound understanding of Chinese society, economy and strategic culture – not only in the Foreign Ministry, but also in universities, companies, state governments and NGOs – can we learn how to make the best of a more China-centric world. Our economic well-being in the next decades depends on it.

Read also:

MBA em Relações Internacionais da FGV no Rio de Janeiro: Encontro com o Coordenador

Palestra na FGV Brasília: “Desafios externos do próximo governo”

Four issues to watch at the upcoming BRICS Summit in Johannesburg