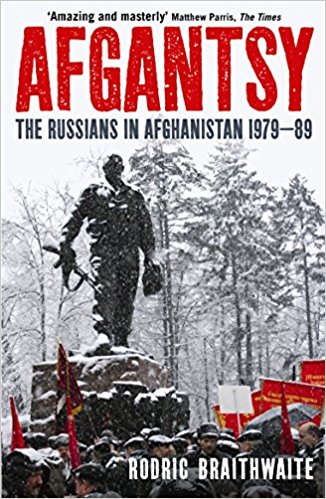

Book review: Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan 1979-1989. By Rodric Braithwaite. Oxford University Press, 2011. 432 pages. US$16.49 (paperback, amazon.com)

——

The Communists did not lack noble ambitions in Afghanistan. “Our aim was no less than to give an example to all the backward countries of the world of how to jump from feudalism straight to a prosperous, just society … our programme was clear: land to the peasants, food for the hungry, free education for all. We knew that the mullahs in the villages would scheme against us, so we issued our decrees swiftly so that the masses could see where their real interests lay … for the first time in Afghanistan’s history women were to be given the right to education … we told them that they owned their bodies, they could marry whom they liked, they shouldn’t have to live shut up in houses like pets.” Large-scale civilian projects were started by cadres of idealistic advisers and technicians all over the country, many coming from Moscow – just like the young NGO workers arriving in Afghanistan after the US invasion in 2001.

When the Communist government, which had come to power in a coup in 1978, crumbled, the mighty Soviet Union was pulled into a conflict many in Moscow believed was unwinnable. The parallels to the United States’ stumbling into Vietnam are remarkable: what began as an observer mission and the provision of military aid turned into a financially and politically draining quagmire on unspeakable brutality without ever having identified Afghanistan as a Russian foreign policy priority. Contrary to what some analysts believed at the time, Soviets were not after access to a warm water port in the Indian Ocean (which would have required invading Pakistan, too). Sheer military capacity led both Washington and Moscow into unnecessary conflicts of limited strategic relevance. As Braithwaite writes,

Step by step, with great reluctance, strongly suspecting that it would be a mistake, the Russians slithered towards a military intervention because they could not think of a better alternative. (p.57)

A lack of policy coordination and infighting in the Soviet bureaucracy helped explain why leading decision-makers in Moscow often made decisions based on political power dynamics in the administration, rather than the situation on the ground in Afghanistan. In what eerily sounds like the United States military presence in Vietnam (or Afghanistan forty years later), a Russian journalist in Kabul at the time shrewdly pointed out,

One of our problems in Afghanistan (…) was that the Soviet Union never had a central office in charge of the various delegations of its super-ministries: the KGB, MID [Ministry of Foreign Affairs], MVD [Ministry of Internal Affairs], and Ministry of Defence. The chiefs of these groups acted autonomously, often sending contradictory information to Moscow and often receiving contradicting orders in return. The four offices should have been consolidated under the leadership of the Soviet ambassador. But there were so many different Soviet ambassadors that none of them had enough time to become thoroughly familiar with the state of affairs in Kabul. (p. 61)

The Soviets’ intention was for the soldiers to depart within six months, leaving a stabilized Communist government in place. Much like the British in the 19th century and NATO in the 21st, the Soviet Army faced little resistance during their initial military invasion, but ultimately failed to pacify (or, as policy makers prefer to say these days, “stabilize“) Afghanistan. Just like to many occupiers before, the Soviets found themselves in a bloody war from which it took them nine years to extricate themselves from. Quite remarkably, as Rodric Braithwaite points out in his masterful account of the Soviet Union’s military occupation in Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989, the Soviet’s capacity to understand or influence Afghan politics remained low throughout, despite spending massive amounts of blood and treasure in the country.

Within weeks of the Soviet invasion, the United States and its allies began supporting Afghan rebels. Under Reagan, the US spent a total of US$9 billion (with very large sums provided by Saudi Arabia, too), which Pakistan mostly channeled to the most radical factions in Afghanistan. The US thus strengthened the Mujahedin, which previously had very little influence and would eventually lead to the rise of the Taliban, who took power soon after the Soviets left.

Like most other foreign occupations, the Soviets faced an insurmountable dilemma, similar to that of NATO a few decades later. As the author points out,

One day, both the Russians and the Afghans knew, the Soviets would go home. The Afghans would have to go on living in the country and with one another, long after the last Russian had left. Even those Afghans who supported the Kabul government and acquiesced in the Soviet presence, or perhaps even welcomed it, had always to calculate where they would find themselves once the Soviets had departed. (p.124)

Indeed, entire sections of the book about the Soviets’ difficulties on the ground — be it finding translators, winning trust of the local population, facing logistical challenges, the frustrating efforts to train a local Afghan army — could be copied and pasted into a book about NATO’s presence in Afghanistan. While Soviet goals early in the war had been to transform Afghanistan into a stable and prosperous socialist country — just like NATO dreamed of liberal multiparty democracy in Afghanistan back in 2002 — conditions on the ground soon made the Soviets less ambitious and more pragmatic. In a famous meeting in Moscow, Gorbachov told the Afghan president “to forget about socialism, to share power with others, including the mujahedin leaders and others who were now his enemies, and restore the rights of religion and the religious leaders.” At the end, Russians lost all interest in the composition of the government in Kabul; all they wanted was a respectable cover for withdrawal. Around 15,000 Soviet soldiers died in the war; among Afghans, the figure stood between 600,000 and 1,000,000.

During the height of the occupation, the Soviets lost almost 150 soldiers per month — not in major battles, but in small and unpredictable ambushes and shootouts. Starting in the mid-1980s, when Russia’s withdrawal was only a question of time, Soviet influence decreased dramatically. Violence spiked and rather than attacking the Russians, the rebels were by then more concerned with jostling for power in the new Afghanistan. “The resulting civil war was (…) more destructive than anything that had happened during the Soviet war.” That is a bad omen for post-NATO Afghanistan.

What makes Braithwaite’s book particularly interesting is his access to personal accounts of Soviet soldiers. These are by no means all negative. Asked back home about how they managed to survive the horrors, one responded that he had fallen in love with Afghanistan. “We did not survive – we lived. We lived life to the full. Everything was interesting, every day was packed” wrote Vyacheslav Nekrasov. “Of course we were young, carefree, quick to make new friends. Even though more than ten years have passed, we are still like a single family of brothers.” (p. 168)

Gorbachev was less sanguine as he ordered the last troops out:

We will leave the country in a deplorable situation, ruined cities and villages, a paralysed economy. Hundreds of thousands of people have died. Our withdrawal will be regarded as a major political and military defeat.

Until the very end of the conflict, the United States supplied the Mujahedin weapons through Pakistan, in direct violation of the Geneva Convention. When the Soviet Union pulled out, Washington stopped paying attention to Afghanistan, even though experts warned that the Soviet stooge Najibullah would soon be replaced by a fundamentalist government, which, the CIA predicted, “will be ambivalent, and at worst … may be actively hostile, especially toward the United States.”

U.S. President Reagan meeting with Afghan mujahideen at the White House

Read also:

Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan, 1839-42